THE SEWING PATTERN TUTORIALS: 4. LAYPLANS AND FABRIC REQUIREMENTS

THE PATTERN ENVELOPE: LAY PLANS AND FABRIC REQUIREMENTS

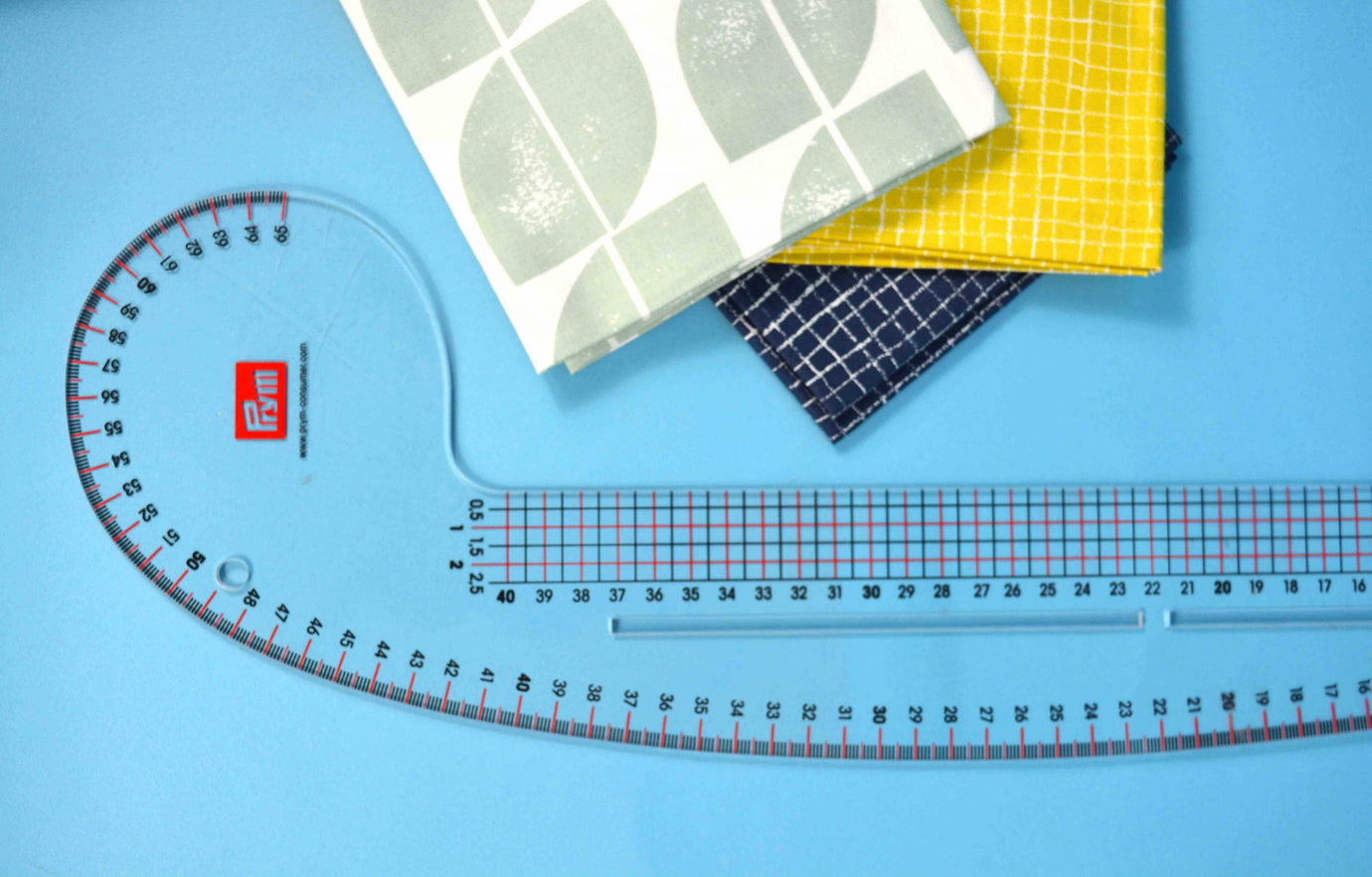

The Sewing Pattern Tutorials is a year-long FREE sewing course where we will demystify dressmaking patterns. We’ll begin with the basics so that if you are new to sewing you can join in from the start. We also know that lots of you want to learn new sewing skills so as the year progresses we’ll begin to cover more complex topics so that you will finish with the skills needed to deal with fitting problems too. In each post we will also have a sewing jargon busting section explaining any terms used that might be confusing. In the first few posts we will explain what all the information on the back of the pattern envelope means and in this post we focus on understanding lay plans and how they affect fabric requirements. Catch up on previous posts in the series here.

What are sewing pattern lay plans and how do they affect fabric requirements?

Lay plans show you the position and arrangement of each pattern piece on the fabric. Most patterns include a lay plan so that you can easily place your pattern pieces within the amount of fabric you have bought for your size. The fabric requirements are the amount of fabric you need to make the dressmaking pattern. If the pattern design is simple, the variation in fabric requirements will only change across different dress sizes. If the design has different variations or uses colour blocking/two fabric types, fabric requirements become more complicated and you will have a more detailed chart outlining the specifics for your size.

Once a new pattern has been designed, the lay plans will be created before the fabric requirements are calculated. It varies hugely between designers but if you are lucky, your fabric requirements have been specific calculated to your size to avoid any fabric wastage. If not, and this applies more to smaller dress sizes, you are likely to have fabric left over and if this is only 10-30cm or so, you probably can’t use it for a different dressmaking project. Not only does an accurate lay plan save you time but it also saves you wasting fabric (and money).

In the example above of Marilla Walker’s Roberts collection sewing pattern, you can see very clearly how much fabric you need and it has been calculated specifically for your size. This has been broken down into main fabric and lining for all versions of the pattern included. For example, if you are a size 4 you would need between 100-200cm of main fabric, depending on the version you were making and 30-35cm of lining fabric.

Do you get different types of lay plans?

This applies more to dressmaking patterns but hopefully your pattern includes fabric requirements for different widths of fabrics. Common fabric widths for dressmaking and other sewing projects are 114cm/45″ (or 112cm if you are Liberty!), 140cm/55″ and 150cm/60″. The narrower fabric widths were traditionally designed for dressmaking projects, whereas wider fabrics were designed for interiors and upholstery projects. These days both widths are printed for dressmaking but the wider fabrics are still usually reserved for interiors because for practical reasons. There is nothing more disappointing that finding a lovely fabric (or worse buying it) and then not being able to make a pattern because the fabric isn’t wide enough. The best advice we can give is to check the fabric requirements for your size and what lay plans these are based on before going shopping.

Some patterns are only suitable for wider fabrics (think circle skirts, you can’t fit these pattern pieces easily onto narrower fabrics) but others are suitable for all fabric widths. There will also be a difference in lay plans for different dressmaking sizes. You can often get away with using less fabric if you are a smaller size because you can, for example, place both front and back bodice pieces next to each other on the fabric, rather than one after the other (using twice as much fabric). For wide pattern pieces such as circle skirts, you can of course shorten them and this could allow you to fit it onto narrower fabrics. We will cover altering pattern pieces later in the year.

How do I interpret a lay plan?

Download your copy of our guide to demystifying lay plans here. First check how the fabric is folded on the lay plan and arrange your fabric to match (is the fold on the left or right?). Usually pattern pieces are cut out on fabric that is folded right sides together, this means that the nice pattern of the fabric is folded on the inside. The wrong side is the side of the fabric without the pattern. The reason the nice side of the fabric is followed on the inside is so that you can mark dart tips etc. onto the fabric on the wrong side with chalk without leaving a permanent mark.

For many dressmaking patterns you need to either cut a pair of pattern pieces e.g. sleeves or cut one piece, on the fold. Not only does it save time to cut, for example, two sleeves out at once but it also gives you a much better chance of cutting out a pair of sleeves that are the same size. Cutting out two or cutting out a pair are distinctly different. A pair gives you two complementary pieces because when the fabric is laid right sides up, one sleeve will be for the left and the other for the right. It is effectively the same as cutting out when the pattern piece is facing you and again when you flip it over and it’s facing away from you. Cutting two, mean two identical pattern pieces. This wouldn’t be very useful for sleeves as your notches would both fit either the left OR right sleeve!

Cutting on the fold also saves time and is more accurate. Instead of cutting all the way around a larger pattern piece, you cut both sides at the same time because the pattern piece has effectively been folded in half. This means that, for example, both sides of your front bodice will be more similar. If you only need to cut one pattern piece out and it’s not on the fold, you need to unfold the fabric and lay it flat, otherwise you will end up with two pieces! Pattern pieces that need cutting on the fold are usually indicated with a line and arrows, pointing to the edge of the pattern piece which should be placed on the fold. Make sure it is positioned right on the edge, if it isn’t close enough you will add several millimetres onto the size of your pattern piece (and then your seams won’t match!)

If you are finding it difficult to know which is the right side, have a look at the selvedge along both sides of the fabric. You should see some small holes in the fabric where the material has been held in place at the factory. The right side is the side where the small holes are raised.

Making the best use of fabric … or not!

Using the minimum amount of fabric for your pattern is not only better for the environment, because it reduces energy spent on creating the product but it also costs you less and reduces waste. Unfortunately by the time you come to lay out your pattern pieces, you may have already bought you fabric. If you do get your pattern first, you could cut out the pieces and lay them out on the floor, using the lay plan in the pattern as a guide and see if you can reduce the amount you need. Mark out the width of the folded fabric (half of 114cm or 140cm). I often do this as I can usually save myself 20cm or more fabric by moving things about. This isn’t so helpful if you are trying to use up your stash though!

It’s also important not to be too over zealous about fabric saving and end up squeezing your pattern pieces on so that the grainline is not parallel to the selvedge. The grainline is the line on your pattern piece which tells you how to place it on the fabric, it must always be parallel to the selvedge. The selvedge is the edge of the fabric and runs along both sides, this isn’t the side that gets cut when you are buying fabric but the two sides perpendicular/at right angles to this. These edges don’t fray as they have been finished in the factory. For accuracy, always measure the distance from both ends of the grainline line (on the pattern piece) across to the selvedge (or folded edge of the fabric), these should be equal.

The grainline of pattern pieces are decided upon by the designer to make sure the fabric has the correct drape. The drape of a garment is the way the fabric looks when it is hanging on a person or mannequin. For example, if a piece of cotton fabric is ‘cut on the grain’ (= in the same direction as the grainline) it won’t have any stretch as it has been cut in the direction that the threads have been weaved to make the fabric (warp threads – lengthwise grain, weft threads – crosswise grain). This would be typical of bodice or dress pieces for a shift style dress (where the straight grain runs in the same direction as the centre front). If a piece of cotton fabric is ‘cut on the bias’ it will have stretch as it is cut at a 45 degree angle to the direction of the threads (and grainline). This would be typical of a collar or facing.

Using more fabric than you need is unavoidable if you want to pattern match though and you would usually do this for plaids and stripes. We have put a couple of links below in the glossary where you can read more about pattern matching fabrics. Top tip – remember to factor in your seam allowances (is it obvious i’m speaking from experience here!?) It is very difficult to estimate how much more fabric you need if you want to pattern match, so you will need to buy a generous amount. As a general rule, the larger the stripes or plaids are, the more fabric you will need to get matching sections.

Sewing jargon explained

Cut on the bias/ Cut on the grain

For example, if a piece of cotton fabric is ‘cut on the grain’ it won’t have any stretch as it has been cut in the direction that the threads have been weaved to make the fabric (warp threads – lengthwise grain, weft threads – crosswise grain. This would be typical of bodice or dress pieces for a shift style dress. If a piece of cotton fabric is ‘cut on the bias’ it will have stretch as it is cut at a 45 degree angle to the direction of the threads. This would be typical of a collar, facing or cutting your own bias strips.

Cut 2 or Cut x1 pair

Cutting out two or cutting out a pair are distinctly different. A pair gives you two complementary pieces because when the fabric is laid right sides up, one sleeve will be for the left and the other for the right. It is effectively the same as cutting out when the pattern piece is facing you and again when you flip it over and its facing away from you. Cutting two, mean two identical pattern pieces. This wouldn’t be very useful for sleeves as your notches would both fit either the left OR right sleeve.

Drape

The drape of a garment is the way the fabric looks/how it falls when it is hanging on a person or mannequin.

Fold line

The folded edge of the fabric or the mark on a pattern piece which indicates where it should be positioned on the fabric.

Grainline

The grainline is the line on your pattern piece which tells you how to place it on the fabric, as it must always be parallel to the selvedge.

Pattern matching

To find out how, see these great tutorials from Tilly and the Buttons and Colette.

Right side/Wrong side

The right side is the pattern side of the fabric. The wrong side is the side of the fabric without the pattern. If you are finding it difficult to know which is the right side, have a look at the selvedge along both sides. You should see some small holes in the fabric where the material has been held in place at the factory. The right side is the side where the small holes are raised.

Selvedge

The selvedge is the edge of the fabric and runs along both sides, this isn’t the side that gets cut when you are buying fabric but the two sides perpendicular/at right angles to this. These edges don’t fray as they have been finished in the factory.